Photo Essay No. 1 (Text, PDF)

| Title | Missouri Madonna |

| Subtitle | - |

| Authors | Katherine Jellison |

| Publication | 2026 |

Text

In January 1939, while working as a photographer for the U.S. government’s Farm Security Administration (FSA), Arthur Rothstein took a picture of a woman and her small child at the side of a rural highway.[1] Under the influence of the famous novel and film versions of The Grapes of Wrath, contemporary viewers might interpret the photograph as an image of Oklahoma dust bowl survivors heading for California.[2] Rothstein’s picture, however, tells a more complicated story of rural America during the Great Depression—a saga that took place at the intersection of race, class, region, and politics.

Rothstein took his photograph not on Route 66 between Oklahoma and California but on Highway 60 in the far southeastern corner of Missouri known as the “Bootheel.” Organized by the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, the mother and child in Rothstein’s photo were two of more than 1,500 displaced persons in New Madrid County, Missouri, who lined both sides of Highways 60 and 61 with all their worldly possessions, hoping to catch the attention of middle-class motorists and the press.[3] They were mostly Black sharecropping families evicted from the land by local White landowners to avoid sharing government farm payments with them. Now replaced by non-resident day laborers who did not qualify for government payments, the displaced sharecroppers put themselves and their meager possessions on display to demand that the U.S. government resettle them in a safe place where they could continue their lives on the land.

Rothstein’s picture of the homeless mother and child was just one of dozens he took during the protest. His pictures, including those of the Missouri Highway Patrol breaking up the protesters’ roadside camps because they were “unsanitary,” soon caught the attention of the federal government in Washington. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt even wrote about the protesters in her syndicated newspaper column “My Day,” noting, “I cannot help wondering about the sharecroppers’ families in Missouri. I fear that human suffering is not confined to Europe these days.”[4] In response, the FSA sent aid to the protesters, and by January 1941, the agency had constructed ten farmworker settlements in the Missouri Bootheel, including almost 600 homes as well as community buildings, water wells, and modern utility systems. The sharecroppers’ protest, and Rothstein’s pictures, had produced results.

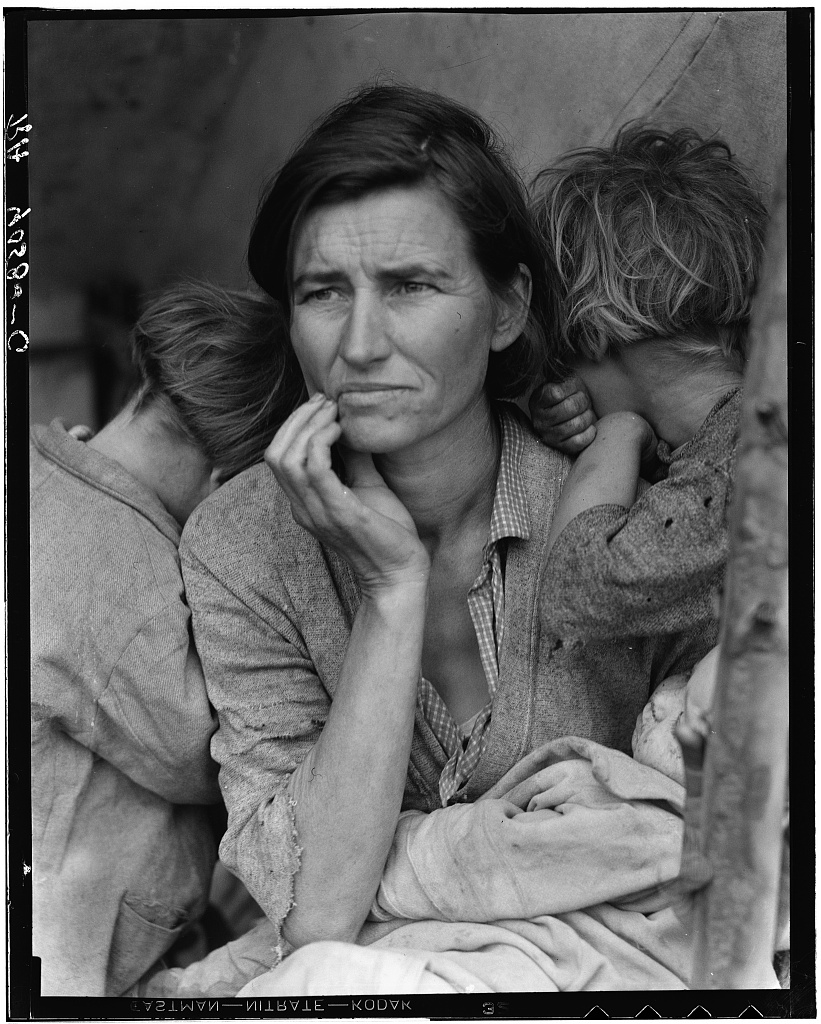

So why is Rothstein’s poignant photograph of the Missouri mother and child, and the dramatic story behind it, so relatively unknown today? In contrast, FSA photographer Dorothea Lange’s 1936 photo of a similar scene—a homeless farmworker mother on a California roadside—has become an iconic image of depression-era America.[5] Unlike Rothstein’s 1939 photo, Lange’s “Migrant Mother” portrait received wide distribution at a time when the Roosevelt administration was focused on economic reform and sought broad public support for FSA relief programs.[6] By 1939, concerned with impending war in Europe, the administration was no longer solely absorbed in domestic issues. In fact, the FSA would soon turn from disseminating pictures of rural poverty to circulating images more appropriate for a nation on the brink of war—photos that celebrated productivity and patriotism in the American countryside.

Timing was not the only factor that caused Lange’s image of depression-era motherhood to eclipse Rothstein’s. The Rothstein photo is an inherently radical image that challenges viewers to face some uncomfortable truths about American society. In Lange’s “Migrant Mother,” the woman at its center, identified years later as Florence Thompson, stares off into the distance as her three young children huddle around her. Although subsequent scholarship has established that Thompson’s parents identified as Indigenous Cherokees, she appears in the photo to be a White victim of economic circumstances.[7] In contrast, the woman in Rothstein’s photo, who remains anonymous, directly returns the photographer’s gaze as a co-conspirator. Against the backdrop of a barren winter cotton field, the solemn but determined-looking Black woman poses with symbols of her motherhood and impoverished domesticity—her baby, a jumble of worn furniture, a bucket of lard, a box of canning jars. As an active protester rather than a passive victim, she collaborates with Rothstein to create an image of racial and economic injustice that needs rectifying.

The portrait that Rothstein and his subject created in January 1939 presents a more complex—albeit to some viewers less sympathetic—picture of depression-era motherhood than Lange’s “Migrant Mother.” In terms of results, however, it is Rothstein’s picture that had the greater impact. Rothstein’s picture of a homeless Black mother and child, along with his other New Madrid County photos, captured the immediate attention of the public and policymakers and spurred the FSA into action. While Lange’s “Migrant Mother” has enjoyed greater fame and longevity as a symbol of the Great Depression, Rothstein’s photo, and the woman in it, merit credit for the noteworthy reforms they inspired. Perhaps, like Florence Thompson, the woman in Rothstein’s photo also deserves a title of symbolic significance. Maybe “Missouri Madonna” would be an appropriate moniker.

References and Credits

[1] Arthur Rothstein (1915-1985) was the first photographer hired for the FSA photography unit and considered one of the most talented photojournalists of his generation. For more about his career documenting American life during the Great Depression, see Arthur Rothstein, The Depression Years as Photographed by Arthur Rothstein (New York: Dover Publications, 1978).

[2] John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath (New York: Viking Press, 1939); John Ford, director, The Grapes of Wrath (1940).

[3] See Louis Cantor, “A Prologue to the Protest Movement: The Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration of 1939,” The Journal of American History 55 (March 1969): 804-822, and Jason Manthorne, “The View from the Cotton: Reconsidering the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union,” Agricultural History 84 (Winter 2010): 20-45.

[4] Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day, January 31, 1939,” The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition (2017), accessed 8/27/2025, https://www2.gwu.edu/~erpapers/myday/displaydoc.cfm?_y=1939&_f=md055177.

[5] Like Rothstein, Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) was one of the most well-regarded photojournalists of her era. The best scholarly biography of Lange is Linda Gordon’s Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009).

[6] The classic study of the FSA and its agenda is Sidney Baldwin’s Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968). For discussion of the role the FSA photos played in that agenda, see James Curtis, Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), and Chapter 4 of James Guimond, American Photography and the American Dream (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991).

[7] See Sarah Hermanson Meister, Dorothea Lange: Migrant Mother (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018).

Biographical notes

Katherine Jellison is Professor Emerita of History at Ohio University. Her books include Entitled to Power: Farm Women and Technology, 1913-1963 (1993), It’s Our Day: America’s Love Affair with the White Wedding, 1945-2005 (2008), and (with Steven D. Reschly) Amish Women and the Great Depression (2023). She has written numerous journal articles and book chapters about topics ranging from the Civil War correspondence of a Massachusetts farm family to US first ladies. Her commentary on gender and politics appears frequently in such media outlets as the BBC, CNN, the New York Times, and the Washington Post.